Sign language, a unique form of communication, does not use auditory cues and relies entirely on visual cues. Hand gestures, facial expressions, and body movements provide an alternative but effective way of communicating, similar to spoken language. While the essence remains the same, the nuances and subtleties of sign language vary significantly from region to region.

For example, some cultures predominantly use one hand for gesture communication, while others use both hands. The meaning of facial expressions also varies from region to region. In some sign languages, however, it serves as an essential component that reinforces and complements the messages conveyed by hand gestures, while in others, it may be used sparingly or not at all.

Etiquette in sign language is not limited to the signs used. It includes the spatial dynamics between communicators, including the distance to be maintained, the level of formality, and expected politeness in communication.

There are about 130 different sign languages recognized worldwide, each taking into account the cultural and linguistic nuances of the native community. Like spoken languages, sign languages can be classified genealogically, grouping them into specific families and clusters.

Among the many sign languages, American Sign Language (ASL) and British Sign Language (BSL) stand out due to the extensive research and documentation associated with them. Today, we will talk about ASL, which has been instrumental in bridging communication gaps and creating an inclusive environment for the Deaf in the United States.

A Brief Overview of History

Sign languages have long been an integral part of human communication, with their origins traced far beyond their official recognition in the twentieth century. Some anthropologists and linguists suggest that hand gestures served as the primary way to convey messages and express emotions before vocal cords became sophisticated tools for creating intricate speech patterns.

It was not until the mid-twentieth century, thanks to pioneering research in the United States, that the richness and depth of sign language was formally identified and appreciated. One of the major figures in this movement was William Stookey. As an aspiring linguist working at Gallaudet College in Washington State, which educated the deaf and hard of hearing, Stookey pioneered an in-depth study of the structural features of sign languages.

His work, The Structure of Sign Language, published in 1960, was a watershed in the field. It emphasized the complexity of grammar, vocabulary, and syntax embedded in sign languages, thus debunking the misconception that they were simply a collection of rudimentary gestures. In 1965, Stockey and his collaborators published the Dictionary of American Sign Language. This comprehensive dictionary brought clarity and structure, offering a linguistic map into the previously uncharted territory of American Sign Language (ASL).

This phase of extensive research and documentation ushered in an era when sign languages were no longer on the sidelines. They rose to prominence in academia, leading to the emergence of a new linguistic subdiscipline dedicated to understanding, preserving, and popularizing sign languages worldwide. As more scholars have immersed themselves in the field, the understanding of sign languages has deepened, emphasizing their role not only as a means of communication for the Deaf but also as a rich linguistic treasure trove reflecting different cultures and histories.

ASL – American Sign Language

American Sign Language, abbreviated ASL, is the primary language of the deaf in the United States and Canada. Its origins can be traced to the influence of French Sign Language, brought to North America in the early 19th century. A key figure in this transatlantic exchange was Laurent Clerc, a French educator. In the 1800s, Clerc traveled to the United States by invitation to establish an educational institution for the deaf and hard of hearing. His efforts culminated in the establishment of the first school for deaf students in Connecticut in 1817. The linguistic patterns of French Sign Language combined with existing local sign systems gradually evolved into what is now commonly referred to as ASL.

On the other hand, a different sign language system prevails in countries such as the UK, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and Ireland. Known as BANZSL, this family of sign languages shares a common origin distinct from ASL. Over time, regional differences and cultural influences have led to the formation of unique sign languages within the BANZSL family, such as British Sign Language in the UK and Australian Auslan.

The development and divergence of these sign languages highlight the rich tapestry of Deaf cultures and the histories of different countries. Each sign language, with its unique gestures, expressions, and grammar, embodies experiences, stories, and traditions, making them an invaluable asset to the world’s linguistic heritage.

Sign languages are not just random gestures; they are structured forms of communication with their own rules and conventions. In American Sign Language (ASL), the alphabet plays a fundamental role, just as it does in spoken languages.

“A” – is represented as a clenched fist, palm facing the interlocutor, knuckles pointing upward.

“B” – open vertical palm, thumb pressed tightly against the space between the index and middle fingers.

“C” – an open palm with the thumb slightly curved outward, creating a letter-like shape.

“D” – the thumb should touch the middle finger, ring finger, and pinky, with the index finger remaining upright. The side of the little finger faces the spectator.

“E” – palm facing the observer, fingers half bent, and thumb pressed horizontally underneath.

“F” – palm held open and upright, fingers close together, with thumb and index finger joined.

“G” – the index finger is pointed to the side, with the rest of the palm facing the interlocutor.

“H” – palm remains closed, index and middle fingers extended horizontally.

“I” – the palm facing the spectator is clenched into a fist, but the little finger is extended upward.

“J” – is illustrated by the same hand position as “I,” but the palm is tilted, emphasizing the direction of the little finger.

“K” – resembles the iconic Victory sign. However, the difference is the pressing of the straightened thumb against the palm of the hand.

“L” – index finger pointing upward, thumb extended outward, other fingers tightly adjoining the palm.

“M” – transmitted as a clenched fist with the thumb placed between the bent pinky and ring fingers.

“N” – a similar approach to “M” is used, but the thumb is placed between the bent middle and index fingers.

“O” – the fingers bend to form a loop, with the thumb and index finger meeting and the palm facing in the opposite direction from the body.

“P” – the index finger points outward while keeping the arm horizontal, with the palm facing downward.

“Q” – similar to “P” but the index finger points downward, and the rest of the fingers are bent inward.

“R” – the index and middle fingers are intertwined, pointing upward, and the palm is oriented toward the interlocutor.

“S” – is indicated by a closed fist, in which the thumb is crossed with the rest of the fingers.

“T” – is indicated by a clenched fist, with the thumb protruding between the index and middle fingers.

“U” – indicated by the index and middle fingers extended upward. These fingers are pressed tightly together, with the thumb parallel to the bent ring finger.

“V” – a well-recognized gesture often associated with “Victory” is used. Here, the index and middle fingers diverge, visualizing the letter “V.”

“W” – three fingers are raised up and spread apart, namely the middle, ring, and index fingers. Interestingly, the pinky and thumb join together to form a unique juxtaposition.

“X” – is depicted as a clenched fist pointing forward. In this gesture, the index finger is bent, and the thumb can be either tucked inward or pointed outward.

“Y” – the hand remains closed, but the little finger and thumb are extended outward, symbolizing the bifurcation of the letter “Y.”

“Z” – demonstrated by the diagonal positioning of the ring finger and pinky, with the index finger also tilted diagonally.

These gestures are not random but derive from a coherent system based on logic and sequence. This specificity ensures that ASL users can communicate effectively without ambiguity. The variety of hand configurations emphasizes the depth and complexity of the language and its importance as a means of communication for many.

Numbers

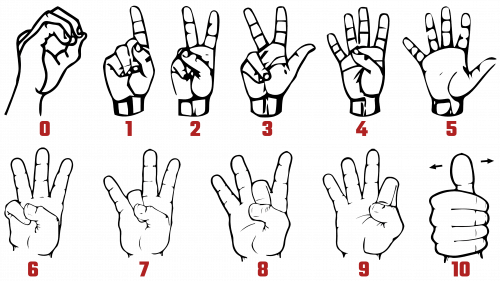

American Sign Language (ASL) offers a unique approach to representing numerical values using hand gestures. A systematic arrangement of fingers designates specific numbers, allowing for effective and clear communication using only the hands.

“0” – the configuration resembles the shape of the letter “O,” achieved by bending all fingers toward the thumb.

“1” – simplicity reigns. The single index finger is extended upward, towering above the closed palm.

“2” – the index and middle fingers are raised upward, clearly distinguishing themselves from their predecessor.

“3” – a slight variation is introduced. The thumb is pushed up, while the index and middle fingers remain extended, contrasting with the closed palm.

“4” – all fingers are spread wide and extended, but the distinguishing feature is the thumb, which is pressed tightly against the palm.

“5” – the entire hand is demonstrated, with all five fingers extended, showing openness.

“6” through “9” have a common theme: all fingers are extended, but each number is indicated by the way the thumb interacts with the other fingers. In the number “6,” the thumb touches the little finger;

“7” – all fingers extended, the thumb touches the base of the ring finger, creating a characteristic shape.

“8” – the thumb shifts and touches the base of the middle finger while the rest of the fingers remain extended, a slight difference from the previous gesture.

“9” – requires more skill. When all fingers are extended, the thumb touches the base of the index finger, which means one less than a full set of ten.

“10” – a unique gesture is used. With all fingers extended, the thumb points upward, a gesture reminiscent of a gesture signifying approval or recognition.

ASL offers an intuitive method of non-verbal numerical communication using these hand shapes. This structure provides clarity and emphasizes the richness and depth of language, meeting a variety of communicative needs.

International Sign Language

Sign languages are as diverse and multifaceted as spoken languages, with each region or country often having its own sign language system. However, among this diversity, there is an international sign language (often referred to as international sign language). Similar to the concept of Esperanto in spoken languages, international sign language is an artificially created sign system.

Although it was developed to bridge communication gaps on a global scale, its use in real-world settings remains relatively limited. At international events and conferences, participants often create a hybrid sign-based communication system. This improvised system is based on similar gestures characteristic of different sign languages. The most iconic, easily understood, and recognizable signs are preferred.

This is explained by two reasons. Firstly, the use of commonly understood gestures allows the preservation of the essence of the message, ensuring the understanding of information by all present. Secondly, iconic signs, easily correlated with their real-life counterparts, minimize the likelihood of misinterpretation.